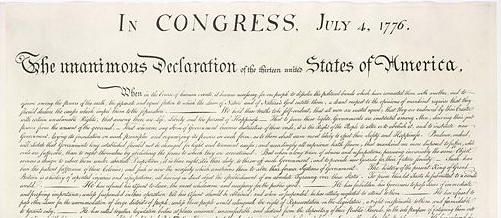

The Declaration of Independence is a great example of collaborative writing. All the elements are there: a writing mandate, plenty of source material, consultation with experts, a tight timeline, committees, key writers of great skill, various drafts, and a three-day meeting, during which the text is edited by many players. The writing team is even told to take care of production. Does it bear any resemblance to the collaborative writing process in your organization?

In the spring of 1776,[1] the idea of independence from Britain was gaining momentum among representatives of the thirteen American Colonies. Inspired by a booklet by Thomas Paine called Common Sense that challenged the authority of Britain and the monarchy,[2] the colonies tasked the Virginia representatives with developing the motion statement—despite the fact that there was no clear consensus among them about the establishment of independent colonies. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented his motion on June 7, 1776:

Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Although it is seconded, there are delays and further debate. Congress would eventually approve Lee’s motion (on July 2, 1776), but at this juncture, it postpones debate and on June 11, appoints a Committee to write a declaration to present to Congress. The Committee of Five includes Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. There are no meeting records, but it seems after discussion about the outline of the document, Thomas Jefferson is tasked with drafting the document. Though relatively young (33 years old), he has demonstrated his considerable writing skills in a political pamphlet (A Summary View of the Rights of British America) and a draft constitution proposal for Virginia. These works are also source material for Jefferson in drafting the Declaration. He shows a draft to Committee members Adams and Franklin who propose some minor changes. They know that not all parts of Jefferson’s document will be accepted by Congress, and they leave in parts that they know could be contentious.

On Friday, 28 June, the Committee of Five presents to Congress the document entitled “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States Of America in General Congress assembled.” The text is presented for discussion after Lee’s resolution is (finally) approved by Congress on Monday, July 2, 1776. During the three-day debate, Congress eliminates text that would have restricted the slave trade as well as statements indicting the British people—dissatisfaction with the King and the British government being the main issue.[TT1]

The Declaration is entered in the Journals of Congress for July 4. The Committee of Five was then told to look after production “to prepare the declaration superintend and correct the press.”

A number of copies, called broadsides, were printed at John Dunlap’s shop on July 4 and 5, 1776, and for the rest of the month of July they are being distributed throughout the colonies and sent to England.

What made the difference was the level of commitment and to working together to get the job done. I’m not sure modern technology tools would have made a lot of difference to the success of the process. It’s fun to think so. See Mike’s blog on collaborative tools and the Declaration of Independence. He references a New York Times article showing the evidence of Jefferson’s change from the word “subjects,” a monarchy-based term, to “citizens,” evoking democracy.

[1] Ann Marie Dubé, Associate Curator, Independence National Historical Park, The Writing and Publicizing of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution of the United States, May 1996. Online book accessed September 13, 2013 at http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/dube/inde2.htm.

[2] Thomas Paine, Common Sense, Third Edition, February 1776. Accessed September 14, 2013 at http://www.ushistory.org/paine/commonsense.

Photo credit: The Declaration of Independence by Roscoe Ellis via Photo Pin as cc